In Conversation with Reza Aramesh

Courtesy of Artist and Night Gallery

Reza Aramesh was born in Iran and is based in London and New York. He holds a Masters degree in Fine Arts from Goldsmiths University, London. His work has been exhibited in both solo and group exhibitions at or presented in tandem with the 56th and 60th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy; the 14th and 15th Bienal de La Habana, Havana, Cuba; Asia Society Museum, New York, NY; The Metropolitan Museum of Art Breuer, New York, NY; Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, ME; SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, GA; Akademie der Kunste, Berlin, Germany; Art Basel Parcours, Basel, Switzerland; Frieze Sculpture Park, London, United Kingdom; Sculpture in the City, London, United Kingdom; Armory Show Off- Site at Collect Pond Park, New York, NY; and MAXXI Museum, Rome, Italy, among others. Aramesh has orchestrated a number of performances in spaces such as The Barbican Centre, Tate Britain, and ICA (all London, United Kingdom). His works have entered public and private collections worldwide, including in Argentina, Germany, Lithuania, Poland, USA, Belgium, Israel, France, Iran, Lebanon, Italy, and the United Kingdom.

I had the pleasure of asking Reza about any global issues he has yet to address in his art, what made him want to be become an artist, his upcoming exhibition at Night Gallery, Fragment of the Self and so much more.

UZOMAH: What are some of the primary materials you use in your sculptures, and how do they relate to your themes?

REZA: The materials I use are deeply tied to the specific epochs of European art history I’m engaging with in a given work. For example, marble allows me to initiate a dialogue with the ideals and aesthetics of the Italian Renaissance—its elevation of the human form, the sacred, and the monumental. If I’m responding to the devotional intensity of 17th-century Spanish art, I might choose limewood, which was historically used for polychrome sculptures in that period. Each material carries a historical weight and offers a tactile bridge between the contemporary themes I explore and the historical context I reference.

Reza Aramesh, Action 224: Study for purple after Otto Pilny ‘The Slaver Trader’, 2023, embroidery on silk, 86 5/8 x 55 1/8 in (220 x 140 cm)

U: How do you approach the spatial dynamics of your sculptures within their exhibition environments?

R: My sculptures often emerge from site-specific projects. The architectural and historical context of the space is not a neutral backdrop—it’s a co-author in the work. I carefully consider how the viewer will move around the piece, how light interacts with its surfaces, and how the history embedded in the space might echo or challenge the sculpture's presence. The spatial choreography is an integral part of how the work is read.

U: Your work engages with media representations of international conflict from the mid-20th century onward. Why is art, particularly sculpture, an effective medium for this engagement?

R: I don’t draw inspiration from conflict imagery—I use it as archival material. These images are often intended for consumption and then swiftly forgotten. By translating them into sculpture, I slow them down, recontextualize them, and place them in dialogue with the canon of European art history. It’s a way to challenge both how we see violence and how it is culturally archived.

Reza Aramesh, Action 237: Study of the Head as Cultural Artifacts, 2025, patinated and waxed black bronze, 15 3/4 x 10 7/8 x 14 5/8 in (40.1 x 27.76 x 37.24 cm)

U: Are there any global issues you have yet to address through your work?

R: Rather than reacting to specific current events, my work speaks to the ongoing, cyclical nature of conflict throughout human history. It’s not about immediacy, but continuity. Through this lens, I reflect on resilience, suffering, and dignity—human conditions that are persistent and universal.

U: How do your sculptures engage with themes such as race, sexuality, and identity in relation to international conflict?

R: These elements exist in my work more as subtexts than overt themes. I’m less interested in framing the work within East-West binaries or identity politics. Instead, I focus on placing myself as an artist—both geographically and conceptually—within the lineage of European art history. That context allows for the subtle emergence of race, sexuality, and power structures through form, material, and gesture.

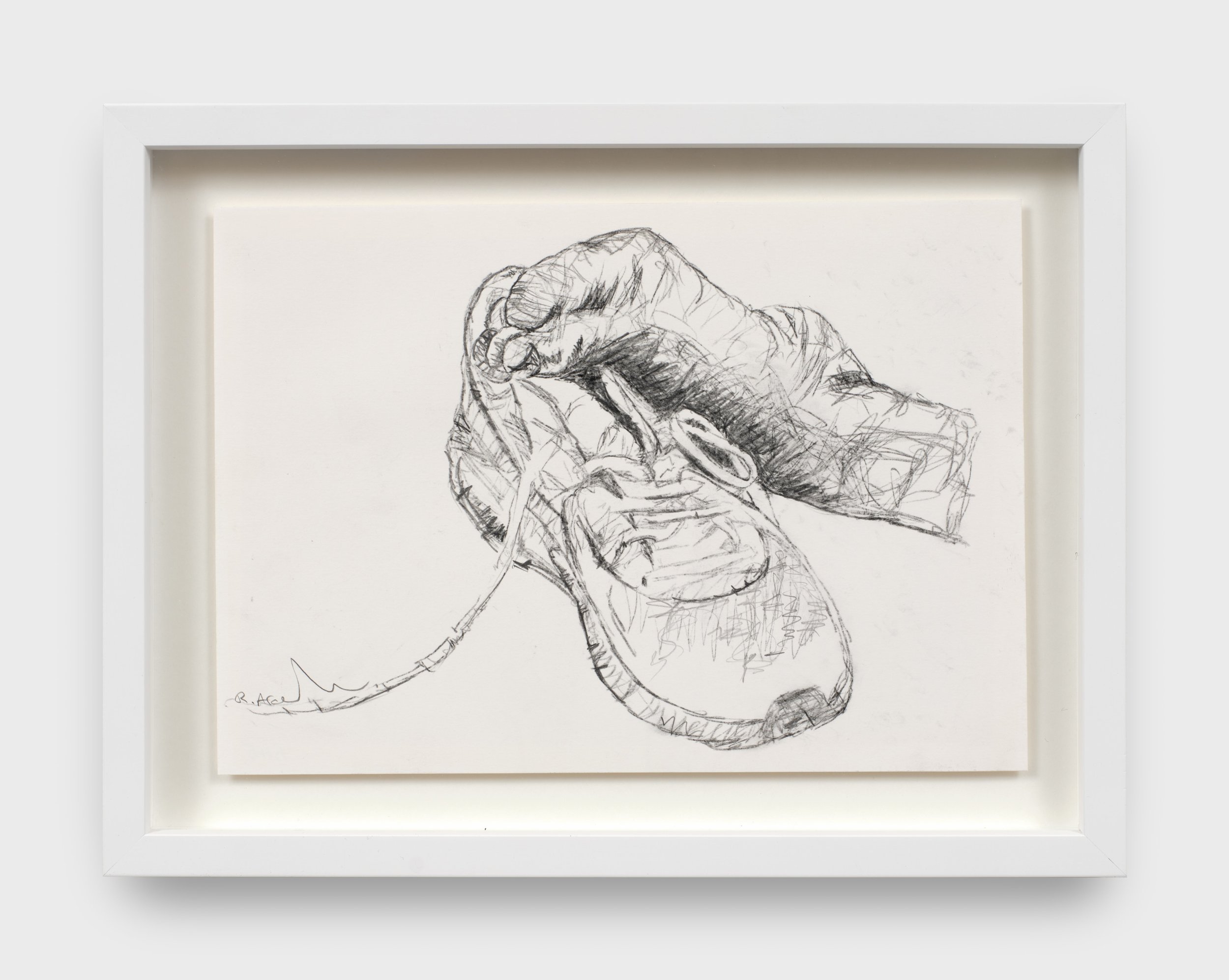

Reza Aramesh, Action 545, 2025, graphite on paper, 11 x 15 x 1 1/2 in (27.9 x 38.1 x 3.8 cm)

U: Much of your work highlights unresolved global issues. Do you believe art can offer a deeper understanding—or even resolution—where traditional media cannot?

R: Media images of violence are consumed rapidly and often without reflection. In transforming those fleeting moments into sculpture, I ask the viewer to pause—to truly look. I don’t propose resolution through art, but I believe in its capacity to provoke contemplation. When we slow down, we might begin to feel the full weight of what is being represented.

U: What first drew you to becoming an artist?

R: Art has always been a means for me to interpret the world. It wasn’t a decision—it was an instinctive response to existence.

Reza Aramesh, Fragments of the Self Action 504: At 11:00 am, Saturday 18 April 2015, 2025, carved and hand polished marble 8 1/2” x 17” x 33”

U: How has literature influenced your work, and what are you reading at the moment?

R: Literature, cinema, and all forms of storytelling deeply shape how I think and create. They offer new frameworks for understanding the world and locating oneself within it. I often read several books at once. Lately, I’ve returned to James Baldwin—his essays, in particular, which articulate the entanglements of race, power, and resistance with such lucidity.

U: Working across sculpture, drawing, embroidery, ceramics, video, and performance, you describe your practice as a succession of ‘Actions'. How do these actions communicate your artistic vision?

R: Each medium I work in demands a different physical and conceptual action. Sculpture may involve carving or molding, but it's also about subtraction and silence. Embroidery is intimate, slow, and contemplative. Performance is immediate and bodily. I don’t see these actions as separate—they form a kind of choreography. Together, they offer a multi-dimensional approach to exploring complex themes. Each action is a proposition, a fragment of a larger conversation.

U: Your upcoming exhibition at Night Gallery, Fragment of the Self, presents four distinct series. How did you conceive them to coexist within a single show?

R: All four series originate from a large archive of reportage photographs—fragments of collective trauma and historical memory. Each medium allows me to respond differently. The marble fragments reflect on the tradition of classical ruins, where incompleteness is not a loss, but a form of survival. The embroideries are in dialogue with Orientalist paintings—I extract a specific hue from a historical painting and use it as the palette for each piece, citing the original work in the title. The bronze head and black-and-white photographs explore the iconography of decapitation, its mythologies, and its persistent symbolism. Finally, the drawings serve as studies for the marble works, but they stand on their own—quiet meditations on gesture and absence. Together, these series create a kind of visual polyphony—distinct voices echoing common concerns.

For more information about Reza’s artwork, please visit his site here. He can also be found on Instagram here. The magazine did a feature on his latest exhibition, which can be found here. Also, an online viewing of the exhibition can also be found here.