An Engaging Conversation with Diego Samper

Courtesy of the artist

Diego Samper is a Colombian artist and designer whose work turns around the dialogue between humankind and nature. As an artist, he works in different media: photography, video, painting, artist's books, and sculpture. With a background in biology and anthropology, his lifelong interest in natural history and tribal cultures are reflected in all of his work.

Traveler, a seven-year permanent residence in the Colombian Amazon (1979-1986), plus many other travels and photographic expeditions to different regions of South America, Central America, and the Caribbean, have given him a strong insight into the tropical rain forests, deserts and mountains, and a good knowledge of some of their indigenous peoples. Other journeys have taken him to North Africa and India. With 45 years of experience in nature and ethnographic photography, he has completed projects commissioned by the Smithsonian Institution Press, National Geographic, Planeta Humano, and other international publishers. His photographs have been printed in more than 30 books (17 of them exclusively of his work). His artwork has been shown in solo and collective exhibitions in Europe, North and South America, Asia, and Africa. With his wife, Marlene, initiated in 2009 the Calanoa Project in the Amazon region, a proposal for cultural and biological conservation of the rainforest that integrates art, innovative design, architecture, communication, and education. Diego has been exhibited widely internationally in galleries, museums, and other art institutions such as Cero Galería,, Gallery Route One, Museo del Oro, Bogotá, Colombia, Museum of Modern Art, Bogotá, Colombia, Ferry Building Gallery; Natural History Museum, Brussels, Belgium; Natural History Museum, Stockholm, Sweden; Natural History Museum, London, England.; Eduardo Síbori Museum, Buenos Aires, Argentina; Center for the Indian Culture, New Delhi, India; National Archives of Canada, Ottawa, Canada, and many more.

I had the pleasure and honor of asking Diego how he finds inspiration, his Tedtalk, how art and activism go hand in hand, and so much more.

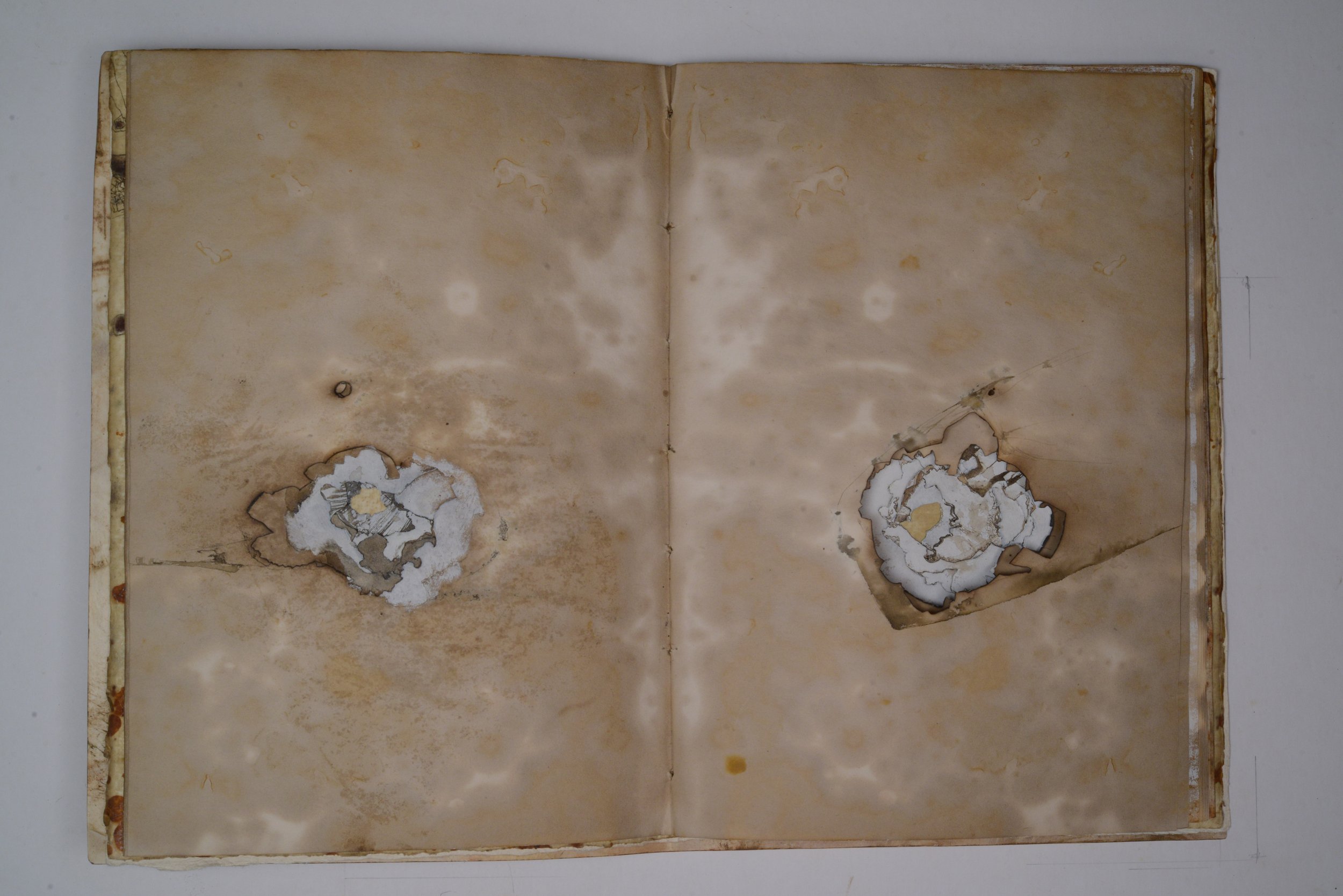

Entomología para Insectos, 2007

UZOMAH: What is your creative process, from the initial idea to the finished piece?

DIEGO: First of all is the subject of inquiry: All of my oeuvres are about exploring nature's poetics and creation's nature. As an endeavor of aesthetic research, the whole process is experimental.

It is Intuition as a way of knowledge: to let it flow, from the first stroke until the last, in a journey without maps, discovering the territory with every step, with no previous image. Bitácoras (Log books) and Cartografías del Silencio (Silence Cartographies), a collection of one-of-a-kind books and monotypes, respond to this idea. Rusted hand-made papers, books, and maps that tell stories or describe geographies without words. Tellurian, these are works that talk about time and matter, sedimentation, and erosion. The decanting stains of rust and the rough texture of the paper become topographies, the territory itself.

diegosamper.com/librosdeartista.html

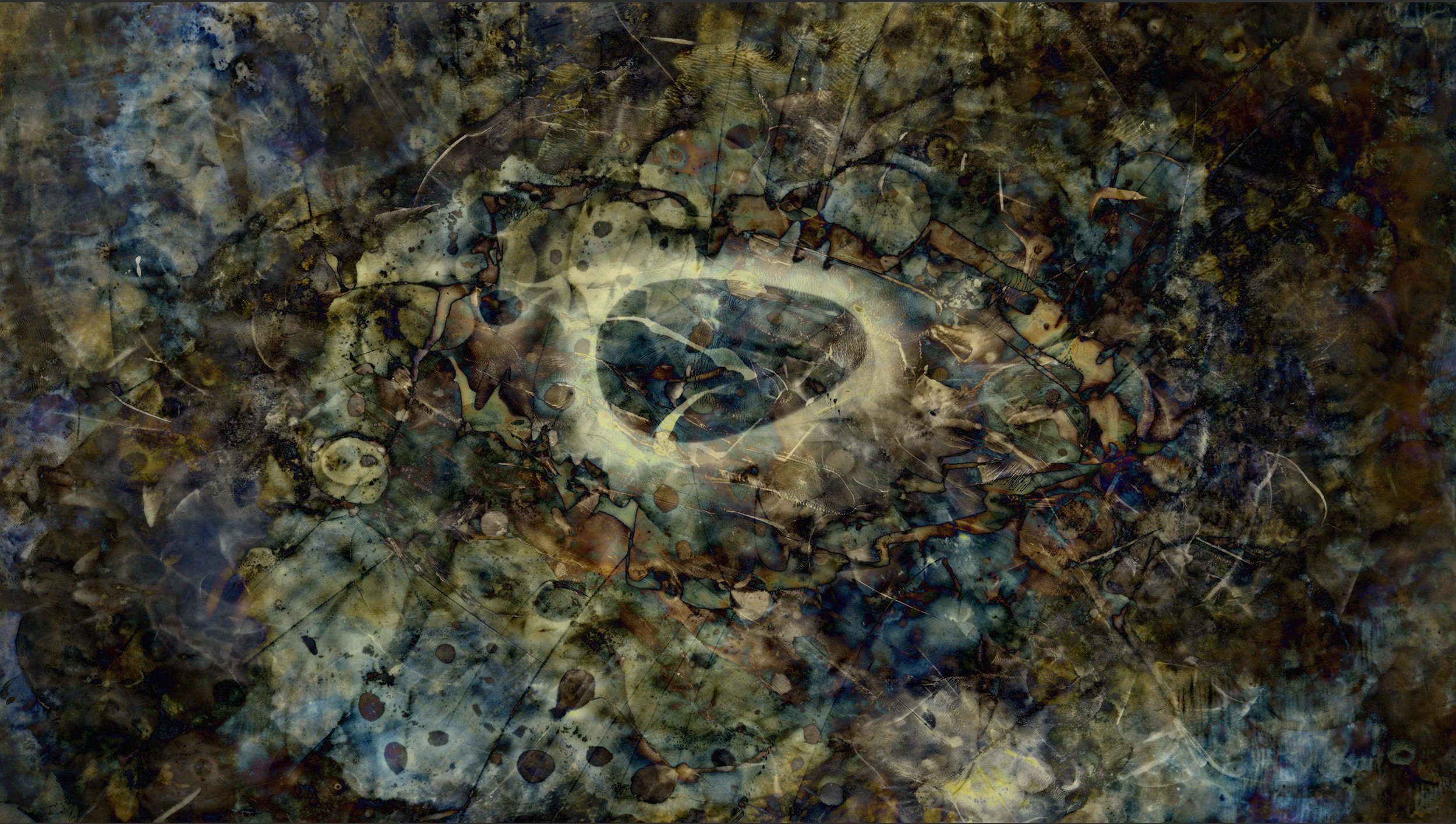

In the study of creation, the discovery of patterns is at the core of it, and for that, there is no better tool than photography. I have always been fascinated by patterns in nature, patterns of growth, flow, and structure that reveal the fractal and holographic essence of nature itself. In fractals, meanders, mycelium, decaying leaves, and eroded sandstone lie the hidden language of nature.

To develop a particular series, I define a medium and set up a format, and usually, a working title that marks the bearings of the series, always open to going beyond or ready to experiment, exploring unexpected turns, and even combining media. Like an extensive series of graphite drawings under the title Entomologías, inspired initially by insects’ anatomy, not trying to illustrate it, but creating free-flowing organic forms that grow and transform permanently, in a constant process of metamorphosis, as is the nature of nature, in each drawing, I would never know how it would grow and evolve and what the final image would be. Each and every time, a surprise, a discovery. I love graphite because it is so direct: consciousness, the hand, the pencil, and the paper.

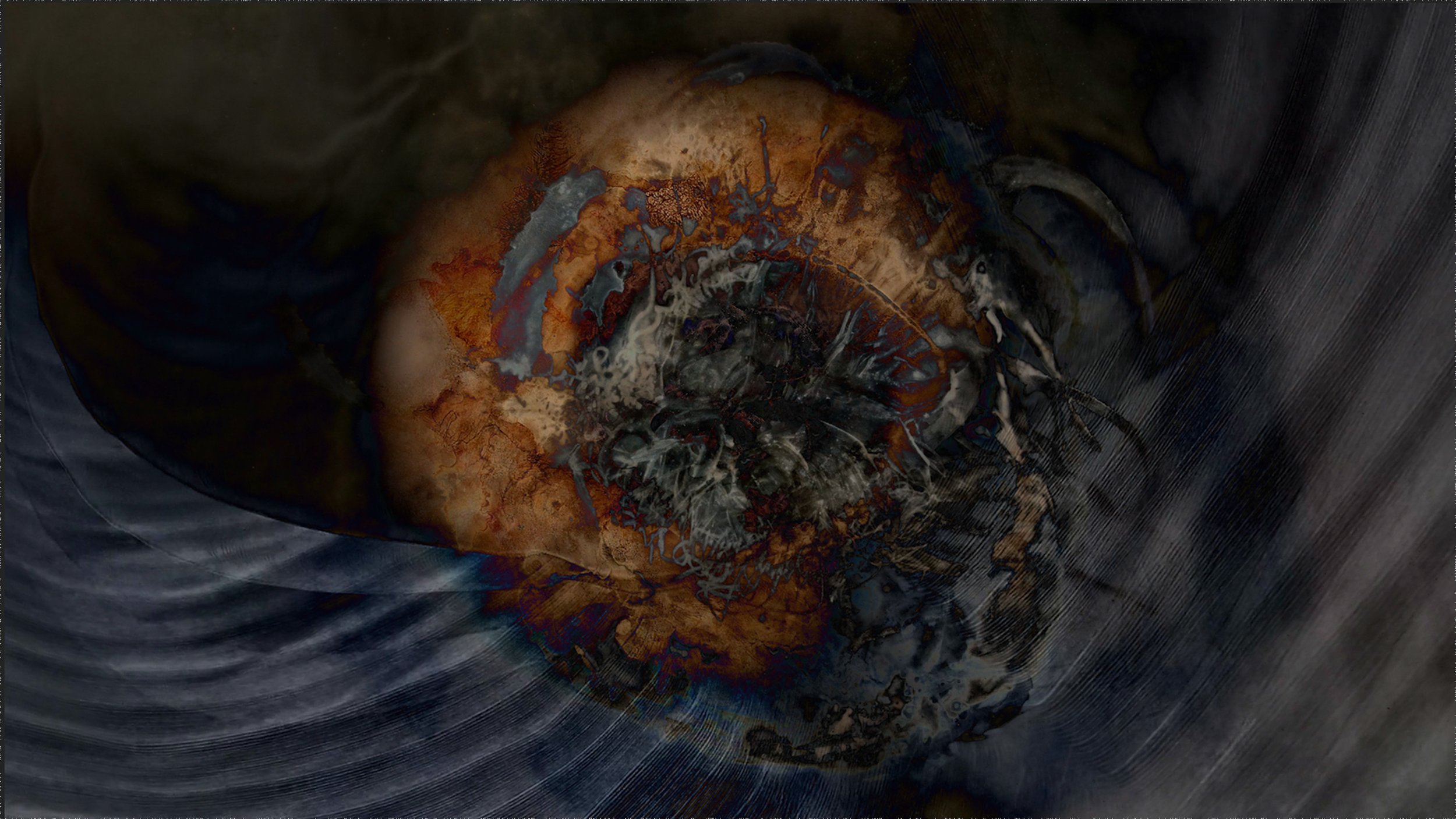

Deriving from these works came Codex, a series of paintings on goat skins, homemade oils applied with hands and fingers, and a rag as the only tool. A primeval experience, caressing the skin and letting forms and shapes appear.

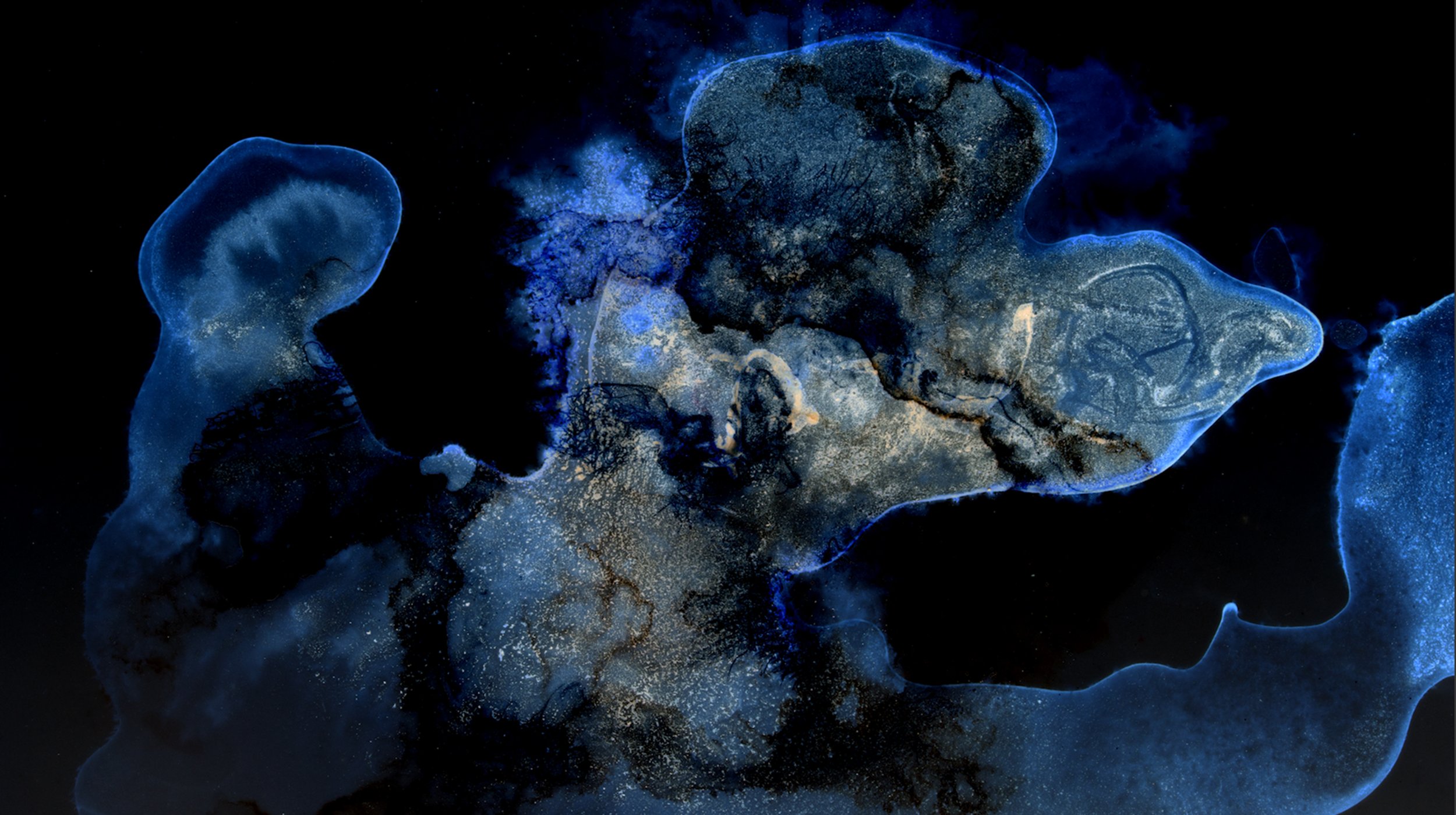

Exploring the nature of time in photography, I developed a series titled Carnaval de los Espíritus (Spirits’ Carnival), photographs made in two instances: the first one a portrait made a century ago, the second one that portrait’s face covered by a mask made out of a natural object, a shell, a seed, a feather. The series reveals the power of transformation that masks can deliver.

Another photographic exploration of time involves hand-held long-exposure images in the Amazon Forest, which became the raw material of my most recent film, Wild Symphony.

Beyond a collection of artworks and series, all of it is a continuum of projects and ideas, an everchanging major oeuvre. These logbooks and drawings, artists’ books, paintings, and photographs are now merging, like water sources feeding a river, into animated films.

Filmmaking is an art form that connects them all.

And films, when not silent, have a soundtrack. Sound and music are other fields to explore.

Soundscapes and field recording have been a constant in my explorations of the natural world. That led to exploring electro-acoustic music, modifying studio recorded sounds, and sometimes later mixing with synthesized sounds or piano music. Soundscapes and music are structured around patterns, and that is what I love to discover. Wild Symphony is a collective project where I have invited professional musicians and indigenous singers to create music together, recording deep in the Amazon Forest and responding to the chants of life.

diegosamper.com/SinfoniaSalvaje.html

Crystal Landscape, photography, 1988

U: Art and activism sometimes appear to go hand in hand; what made you want to combine the two?

D: Art is a powerful tool of transformation, both for the artist who practices it and for the ones who experience the artwork. And Art can transform societies and communities.

Since the beginning of my journey as an artist, Art -as a continuous search for beauty- has been a way to explore the world around me, and the Amazon Forest has been at the center of it since the beginning. My first trip there, when I went to live in a remote indigenous village, was deeply transformative. Guided by a Cubeo shaman, I had a brief glimpse of the infinite well of wonder that offers life in this forest,

On my return, I started to work seriously in photography, a powerful tool to explore and study nature and to record the way of life of the ancestral people of the forest. At that time, I was studying Anthropology. Later, by publishing books on natural history and tribal people, I could contribute to a better understanding of the paradise we live in and an appreciation and respect for the Other. With my wife and daughters, we are running the Calanoa Project, a conservation venture that aims to contribute to the cultural and biological conservation of the Amazon—our small and humble grain of sand to solve the actual environmental crisis.

Art is central to this project. At a community level, we promoted a Mural Art project in a Tikuna village, where all the houses were painted with murals related to their clans or mythology. Parallel to that, we facilitated a photographic exploration of the village through the eyes of children from 6 to 11. The result is that the village became an attraction for visitors to the Colombian Amazon and prepared the ground for a community-run tourism enterprise.

U: What is art's essential message that may be hard in another method?

D: Artistic expression, as a metaphoric language, delivers the transforming power of poetic expression, be it with words, sounds, images, or whatever. It can reveal the essence of things in a way that other languages or methods of inquiry cannot do.

It can reach into the innermost fibers of ourselves and, by resonance, make us vibrate with the world around us—perception, emotion, and a kind of knowledge beyond the spoken language. Art is imagination as a way of creating the world. Art is a way to give sense to it.

U: What advice would you give an artist that wants to use art to present issues and ideas that affect their community?

D: Use the local languages: imaginaries, words, and music … Imprint them with the distilling of your dreams.

Follow your intuition.

Awake in the viewer’s imagination and wonder.

U: Where do you find inspiration for your artwork?

D: In the poetics of nature, which is everywhere you look around, at any scale.

Carnaval de los Espíritus, 2020

U: What is your favorite part of the artistic process and why?

D: Those moments of wonder and awe when you can see yourself just as an instrument that resonates with the magic of life.

U: What's your least favorite?

D: Promotion

Bitácoras, artist book, 1994

U: Your TED Talk, The Forest Within, discusses your time in the Amazon alone. What were you reflecting on about humanity and your time in isolation that still impacts you the most?

D: The forest within is a metaphor for the forest inhabiting my soul. It is the awakening of the wild within myself, the natural being in each of us that hears the pulse of the land and beats with it.

It was my third time in the Amazon, and I long desired it. This time I didn’t arrive as a traveler. I was coming to live in the forest, my dream since I was a kid. With the help of two Makuna friends, we built a dug-out canoe in the Apaporis River and paddled down for four days to the last cascades of the river, where they helped me to build a very basic cabin. A palm roof with no walls and an elevated floor made of palm lathes. Once done, they left, and I stayed there for two years.

I was alone, the closest neighbors at several hours paddling, and a village where I would occasionally send a message to my parents (survival proof) and get supplies. It was an experience of living a simple life with just the essential elements for survival: a hammock, a few pots, a few essential tools and fishing equipment, and a canoe.

No books nor radio. After six years of university studies, I went there to wash my brain and start anew.

I just wanted to be there, deep in the forest. Opening my senses, learning how to see, listen, and perceive with the whole body and soul. Learning how to know through silence, the silence of the mind, beyond words. After the years, the wilderness inside, the forest within, is what remains and guides me.

We all are nature.

West Coast series #36, watercolor, 2010

U: When designing CALANOA, how did you incorporate the forest into the making of the residency?

D: The design of the place and the architecture respond to the conditions of the humid tropics. The settlement is deep in the forest, by the shores of the Amazon River, and the big question has been how to incorporate us into the forest.

Calanoa means the manifestations of the spirit of nature, so a relationship of respect and reverence with the place starts with its name.

With a holistic approach, the different aspects of creating the settlement are related to the forest and the communities around it. Calanoa is a laboratory of architecture and landscaping, of gardening as well as gastronomy, of restoration of a cultural landscape and of a natural landscape: A restoration of a dialogue with the natural world around us.

The exploration of building materials has led to a cross-fertilization of architecture, art, and gardening. Due to the high humidity of the place, canvasses that were hung as light walls to provide privacy in the cabins, after a while, started to grow the most beautiful lichen gardens. I was already exploring big format paintings of river silt and clay on canvas, meanders created with the flow of matter over the surface. This led to a series of silt-soaked canvasses hanging in the forest, creating a vertical garden for moss and lichens to grow. Some of these fabrics have been incorporated into the architecture, creating rich translucent walls that act as screens where the lights and shadows of the forest are projected: a shadows’ theater on a living screen.

Autarchy (self-sufficiency) is at the core of our philosophy. We look to solve all the challenges of living in the forest with local resources when possible. That means not only using local materials and techniques but tapping into the ancestral knowledge of the Amazonian people.

To live in the forest is to live with the forest and allow it to dwell in your soul.

Yoni, photography, 2002

U: What is art's essential message that may be hard in another method?

D: Artistic expression, as a metaphoric language, delivers the transforming power of poetic expression, be it with words, sounds, images, or whatever. It can reveal the essence of things in a way that other languages or methods of inquiry cannot do.

It can reach into the innermost fibers of ourselves and, by resonance, make us vibrate with the world around us—perception, emotion, and a kind of knowledge beyond the spoken language. Art is imagination as a way of creating the world. Art is a way to give sense to it.

U: What are you working on next?

D: Some of my projects are ongoing, like making music with the forest or building Calanoa. For the last few years, I have focused on filmmaking and editing a collection of experimental short films under the title Cosmogonies. Audio and visual poetry, short dreamlike wordless stories of the origins of the world, because we create the world every night, in our dreams…

For more information about Diego’s artwork and ongoing projects, please visit his site and follow him on Instagram.