A Substantial Conversation with Boris Torres

Photo Credit: Ira Sachs

Boris Torres: (b. 1976, Ecuador) received his BA from Parsons School of Design, MFA in Fine Art from Brooklyn College, and MA in teaching from City College Of New York . Torres’s work has been part of numerous museum and group shows, including the Bronx Museum of Art, Tacoma Art Museum, and Leslie-Lohman Museum, NY. A 2019 recipient of the Leslie Lohman Museum fellowship, his work has been featured in Hyperallergic, reviewed in the New York Times and included in several critically acclaimed films such as Tu Me Manques, Keep the Lights On, and Love is Strange. In Art & Queer Culture, by Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer, Torres’s work is included in a historical survey of significant work on culture and sexual identity from the last 125 years. Mr. Torres is represented by Kates-Ferri Projects.

UZOMAH: How does your creative process work into a regular day for you?

BORIS: I like to work when I do not know what I will create next. My day begins with a craving to fill this unknown, and then I begin to look for images I have collected over the years until I find something that leads to something, and so on, and then I have this feat ahead that could last a day or weeks. On the days I have scheduled a sitter, my work process is the opposite. It is planned weeks ahead, on a certain day, and for a measured amount of time, and it’s a collaboration between me and the sitter; this is a different way of working that I welcome.

U: How can the art world be more receptive and willing to display and exhibit more works by queer artists and artwork depicting what it means to be queer?

B: I think the art world is becoming more receptive and willing and has a long way to go. An artist’s work is ruled by its commercial value, and that guides who galleries show. I have been told often that paintings of dicks don’t sell. I believe the art world will change when there are queer people of color owning and running the galleries and influencing the market.

U: What are you most proud of in your career?

B: This is a hard question because I have been proud to show at certain galleries and museums that have made me feel validated. But I think the most meaningful moments have been when I have created work that I was afraid to make and that was too revealing of myself, and now in hindsight, I’m proud I did it.

“Margit,” by Boris Torres, oil on panel, 11x14 inches, 2023

U: How has making art helped you understand more about yourself, life, and society?

B: I took a class in college on Latin American women artists from the ’40s and on- and that class changed my life. These artists made their work fearlessly and at a great disadvantage living and working in a world dominated by male artists. People like Frida Kahlo and Ana Mendieta were unapologetic about their sexuality and did work that made people uncomfortable. These artists gave me permission to do my work without shame. I would then paint what was true to me, I would paint the things that excited me, and that terrified me. I could reveal things about myself and the world that I could not do so through words.

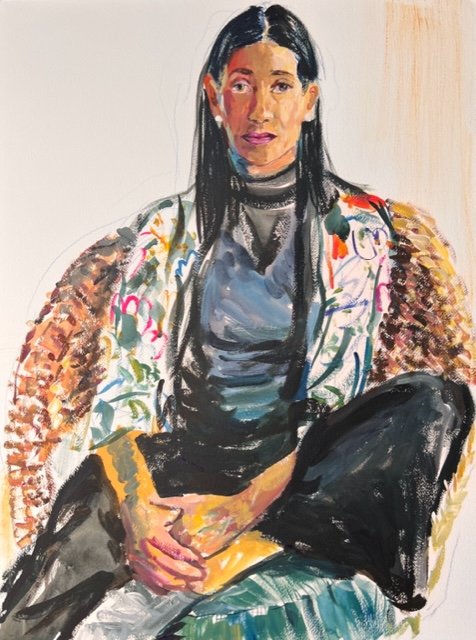

“Portrait of Anamaria Garzon,” by Boris Torres; acrylic on paper, 18x24 inches, 2022

U: If you could have any artist living or dead, paint your portrait, whom would it be and why?

B: I would have Alice Neel paint my portrait. I have learned from her work over the years, and like her, I desire to paint the people around me. I can imagine talking to her in my sitting, hoping she finds me interesting and seeing what she captures of me through that intimate encounter.

U: Your artwork also explores life from a Latin American perspective. How do you engage with colors to show the vibrating liveliness of the culture you come from?

B: I love vibrant colors; Ecuador has given me that aesthetic. As a child, I grew up in a town located in a cloud forest full of colorful buildings surrounded by colorful plants and animals unique to that area. Color is part of my artistic language, a mix of my Ecuadorean background and having grown up in New York.

“Franz,” by Boris Torres, oil on panel, 11x14 inches, 2022

U: What is the biggest misconception that people have about your work?

B: A misconception is that my work doesn’t fit a specific category because I work with different mediums and techniques and have various styles. Although it may not seem obvious at first, I see all my work connected because it often deals with my interest in culture, history, and community. I love Joe Brainard’s work for a similar reason, he was a poet who also made different works of art with different materials, and it all works together. I love the freedom of letting my creativity guide me instead of the other way around.

“A wounded man,” by Boris Torres, oil on panel, 10x14 inches, 2022

U: If you could sum up your artistic statement in one word, what would it be and why?

B: Sexy

“Portrait of Helen and Sydney” by Boris Torres; acrylic on paper, 18x24 inches, 2021

U: You depict portraits of various types of people and backgrounds. How do you create such realistic art that is true to the image?

B: The most realistic aspect of my portraits happens when the viewer senses something human coming from the portrait; perhaps the viewer senses that the person in the portrait is reserved or open, feeling sadness or relaxed or thinking about something. I use loose brushstrokes to paint the model; these gestures can transmit a mood of something more true than a photo-realistic rendering.

For more information about Boris’s artwork, please visit his site. Please follow his Instagram and Twitter.