An Intriguing Conversation with Ehren Tool

Photo Credit: Argil Tool

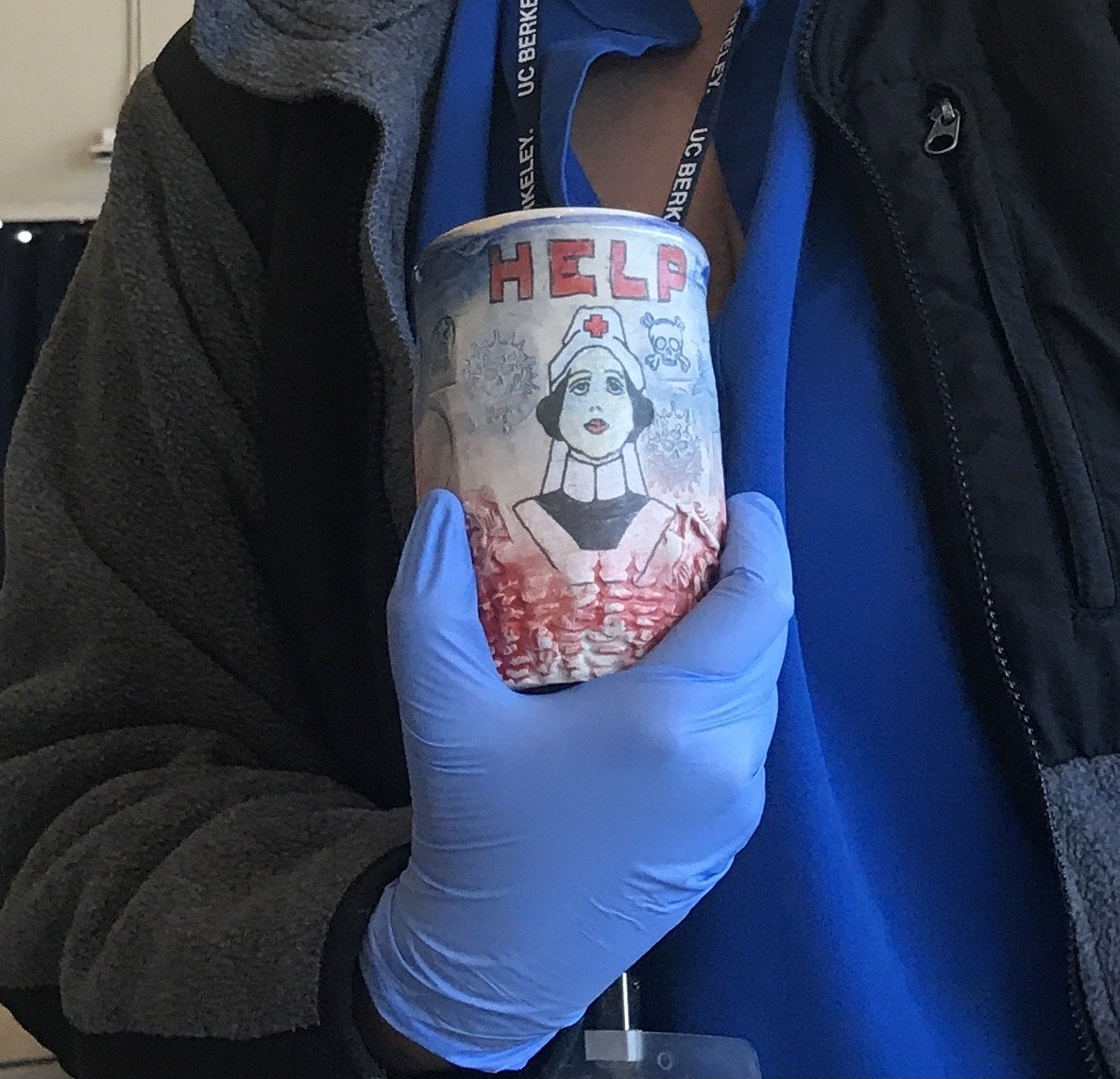

Ehren Tool is an American Ceramic Artist and Senior Laboratory Mechanician at the Ceramic Department at the University of California Berkeley. Being in the Marine Corps and his return to civilian life helped foster his work as an artist. Known for his signature cups, Ehren has made and given away over 20,000 cups since 2001. His cup-making and classes have built a lasting and meaningful conversation that promotes the arts, community, and his belief that peace is the only adequate war memorial while honoring soldiers. Ehren has shown his work in the US and Europe in artistic spaces such as the Oakland Museum of California, Craft and Folk Art Museum, Berkeley Art Center, Bellevue Arts Museum, and Clay Studio. He was chosen by the philanthropic organization United States Artists to be a 2010 USA Fellow. He received his MFA from the University of California, Berkeley, and his BFA from the University of Southern California. I had the pleasure and honor of asking Ehren about using Art to explore the experiences and choices he has gone through, the biggest lesson he learned while being in lockdown, and so much more.

UZOMAH: How has your return to civilian life from being a veteran in the Gulf War impacted your artistic process?

EHREN: I did not have an artistic process before joining the Marines. I think the disappointment of what I could accomplish in the Marines gave me the confidence to pursue an art career. I joined with all kinds of good and noble intentions—the gap between what I thought I was going to do was vast and painful. I have aspirations, unrealistic aspirations, for my work. I say, "I just make cups," partly as self-defense. My cups may not be Art, but they are food safe and hold liquid.

"You say you can't create something original? Don't worry about it. Make a cup of clay so your brother can drink." -Jalal Al-Din Rumi.

U: How do you take what you have seen in war to explore through your Art?

E: My father didn't talk about his war. My grandfather didn't talk about his war until I returned from my war. To be demonized or idolized for something you did or didn't do in a context you can never explain is difficult. Not talking also has its consequences. While deployed, my father sent me letters and suggested I avoid looking at corpses. I'm grateful I followed his advice. One of the issues I try and talk about in my work is building community and making space for people to speak about unspeakable things. The military does not have a corner on the trauma market. My time in the Marine Corps was as close as I have ever experienced to the rhetoric of America. A "melting pot," a "meritocracy." I served with folks from all kinds of backgrounds. I miss and try to recreate the camaraderie and community I had in the Marines. "Locate close with and destroy the enemy by fire and maneuver in the Marines." Now: Locate close with and destroy the enemy through conversation, empathy, and shared experiences. The community of folks who respond to my work is much more interesting than the objects themselves. I've made cups for Vets from WWII to today's wars. I've made cups for Gay, Trans, Black, White, Native, Asian, Disabled, and all kinds of Vets. We can train together, fight together, die together, and be buried together, but there is no place in America we can all live together. If folks care about Vets, how can they not care about their communities? The Navajo Code Talkers saved countless Marines' lives in WWII. There is still no clean water on the reservation! Blacks have served in every war, and still, a black man 18-30 is statistically safer in the Marines in Afghanistan at the worst part of the war than in any large city in the US. All the wars are lauded as protecting American lives. Universal health care would do a better job of protecting American lives.

U: What do you think about having art therapy as an option for veterans who have an addiction or face criminal charges due to mental illness and illnesses related to their tour of duty?

E: I think anything that builds community can be useful. I'm not sure whether my "art practice" is therapy or a sign of a mental illness. I need to make the work I make. I would make it regardless of its reception. I am grateful beyond words when my work resonates with other people. I think most healthy practices can be healing. Setting and attaining goals can be very helpful. The military structure can be burdensome, but it is also fairly easy to navigate. The civilian world is only about money. Loyalty, honor, and sacrifice are all punch lines. Your bank account defines you more than anything else. Ours is a sad, selfish society. Being able to help other folks has helped me more than anything else. Making a cup is a small gesture for a widow or grieving mother, but it is something that I'm honored to do. I'm so grateful to be able to do what I do. I am on the Tarzan financial plan (swinging from paycheck to paycheck). I have a good day job that provides healthcare for my family and access to community and kilns. I am so grateful to be able to give and not sell work to folks who do not resonate with the work. I once asked Emory Douglas what he thought success was. He answered immediately with great confidence, "when your work resonates with the people." I have yet to have a show opening where someone didn't cry. An Irish bartender told me, "A burden shared is a burden halved." I hope the cups can be touchstones to start conversations about unspeakable things. Polite society is a hard place for people who suffer from trauma.

U: Can you explain Peter Voulkos's influence on your work?

E: I'm not sure his influence was good for me. The legend of the hard-drinking tormented artist is something I aspired to, or at least I connected with. It was a path I was following. As I have been working with Vet Art and exposed to stories of other Vets, I realize that so much trauma is unrecognized, untreated, and often celebrated as manly or macho. I think it is possible to make strong work without torturing the people who love you and destroying yourself.

U: How does your preferred choice of heating your projects change in choosing colors to make them?

E: The science around ceramics has changed a lot in the last 20 years. Colors that had previously only been possible at low temperatures (1945F) are now possible at temps as high as 2350F. I have been trying to reduce my carbon footprint by using electric or more efficient downdraft gas kilns. My color palette is not restricted by temperature.

U: How do you use Art to explore the experiences and choices you have gone through in life?

E: I was told that I am not making Art; I am simply recording or documenting. I'm not an Art Historian, so that is not my problem. I think our obligation is to do what we believe. If you are a painter and painting is dead, you should still paint. I do not have a solid plan for what I am doing. When someone gives me an opportunity, I try and make sure they do not regret it. Some of my biggest regrets are things I did because I was told to. It felt bad at the time and felt worse years later. I do feel like I am a witness to our time. I hope the cups can be little notes to future generations. "We've been through this. We made it. You'll make it also." Of course, we will not all survive. The cups will all one day break. I hope folks will enjoy some good beverages in them before they do.

U: What is the essential tool, object, or instrument in your studio, and why?

E: I was asked a similar question on a meritorious Corporal board. What is the essential tool, object, or instrument in Post One, and why? I said to the radio, "The Marine." I didn't feel like I was a piece of equipment. I still got promoted meritoriously.

I guess for your question, I'd say the clay. Clay is decomposed granite. Plastic clay is very responsive and malleable. Similar to combat. Once the clay goes through the fire, it will be changed for the next 500,000 to 1,000,000 years. War's consequences last much longer than the actual combat. While I was in France for the 100-year anniversary of the beginning of WWI, the director of the residency said, "there are parts of the forest she is forbidden." There are still unexploded bombs and mines from WWI on the ground there. There is something about clay and the process that I am deeply attracted to.

U: What has been the biggest lesson you have learned while being in the lockdown about your creative process?

E: I would do fine on an island or living in semi-isolation as long as I had a few friends, family, access to my studio, and everything in it. I love my family, dog, and our house and would be fine being "trapped" there. This last week 500 cups left my studio for various shows and events. It was so much fun. Making the cups is important to me. Sharing the cups is such a gift to me. Having the cups leave my studio and be adopted by folks the cups resonate with means so much to me.

It really is all about community!