A Winsome Conversation with Alfredo Arreguin

Photo credit: Kevin Cruff

Alfredo Arreguin is an internationally renowned Mexican artist based in Seattle, Washinton. He is recognized as one of the originators of the Pattern and Decoration movement in painting. He has a long and distinguished list of accomplishments. In 1979, he was selected to represent the U.S. at the 11th International Festival of Painting at Cagnes-sur-Mer, France, and won the Palm of the People Award. In 1980 he received a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. In 1988, in a competition that involved over 200 portfolios, Arreguin won the commission to design the poster for the Centennial Celebration of the State of Washington (the image was his painting Washingtonia); that same year, he was invited to create the White House Easter Egg. Perhaps the climactic moment of his success came in 1994 when the Smithsonian Institution acquired his triptych Suefio (Dream: Eve Before Adam) for inclusion in the National Museum of American Art collection. A year later, in 1995, Arreguin received an OHTLI Award, the highest recognition given by the Mexican government for the commitment of distinguished individuals who perform activities that contribute to promoting Mexican culture abroad. More recently, his success has been cemented by an invitation to show his work in the Framing Memory: Portraiture Now exhibition at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

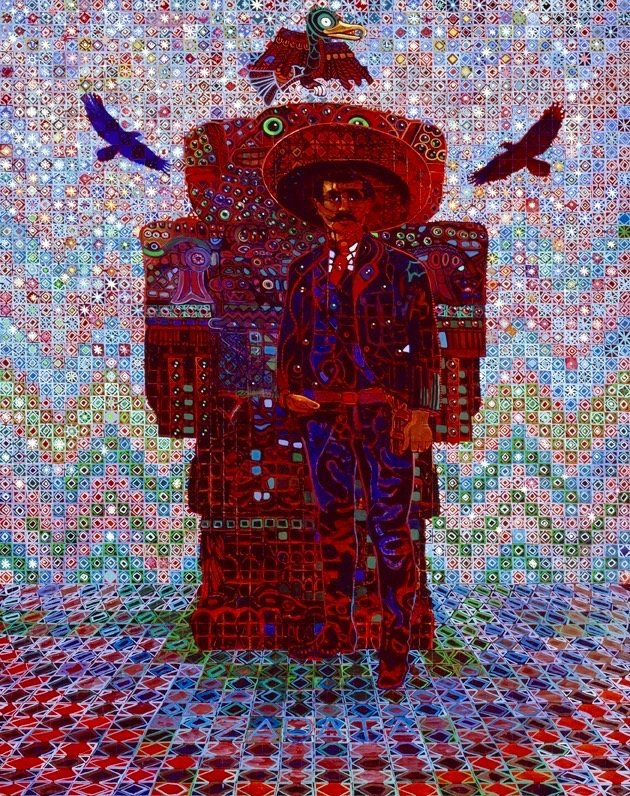

One of his paintings included in this show, The Return to Aztlan, will remain in the permanent collection of the Gallery. Arreguin's work is now in the permanent collections of two Smithsonian Museums: The National Museum of American Art and the National Portrait Gallery. In 2000, he received a Distinguished Alumnus Award from the University of Washington's Multicultural Alumni Partnership, which also established The Alfredo Arreguín Scholarship in 2006. In 2007, his fame was cemented when he was invited by the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery to show his work at the Portraiture Now: Framing Memory exhibition in Washington, D.C; One of his paintings included in the show, The Return to Aztlán, was kept in the permanent collection of the Gallery. In 2008, the University of California at Riverside honored him with the Tomás Rivera Lifetime Achievement Award.

In 2011, he received a Timeless Award from the University of Washington's College of Arts and Sciences. In January 2013, the State of Michoacán organized an Homage to Alfredo Arreguín "to recognize his distinguished trajectory in the arts and his dedication as a promoter of Mexican culture at the international level." The homage included an exhibition of his works organized by the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo ‘Alfredo Zalce’ at the Centro Cultural Clavijero. In 2014, Arreguín was invited to participate in a collective show, Imagining Deep Time, hosted by the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D. C. More recently, in 2015, a sample of his work was shown in three solo exhibitions in Spain; first at the Palacio del Conde Luna in León, then at the Museo de América in Madrid, and lastly in the Museo Provincial de Cádiz.

In 2017 he was awarded the keys to the city of Morelia, an honor only shared with Pope Francis. In 2018, the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art hosted a retrospective exhibition of his works, Alfredo Arreguín: Life Patterns, and more recently, in 2019, his painting The Return to Aztlán, which forms part of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery's permanent collection, was featured in the collective show, Emiliano. Zapata después de Zapata, at the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes, in Mexico, D.F. Alfredo Arreguín nació en Morelia, Michoacán, México, y se formó como artista plástico en

His twelfth solo exhibit at the Linda Hodges Gallery is being exhibited till August 27, 2022. Concurrent with the exhibition is his museum show, "Arreguin: Painter from the New World," at the Museum of Northwest Art (La Conner, WA) through October 9. I had the pleasure and honor of asking Alfredo about growing up in Mexico, his favorite musicians to paint to, what a typical day in the studio looks like for him, and so much more.

UZOMAH: Can you explain the importance of artistic movements, such as the pattern and decoration movement?

ALFREDO: Well, first of all, I had this art historian and critic called David Shaff in Washington, D.C., and when he saw my work, he told me that I was the first pattern painter. A lot of critics don't believe that I am a pattern painter. I'm more of a magic realist than a pattern painter because the pattern movement doesn't have a history. When you do, the painting is more or less just patterns with as much content other than the pattern itself. I'm an artist who does not belong to any movement. I just paint what I feel. Then I get all these critics and art historians trying to put me in a movement or style I don't belong to.

Really, at first, I was complimented by the fact that they told me I was the first pattern painter. Still, since then, there was the National Museum of American Art curator that his opinion was that nobody paints like me, that I'm a very original painter. That's why I am much happier than the title of pattern painter. The reason that I love patterns is that when I was a child, I was fascinated by going to the Mexican markets and with my grandma. She would take me to the market, and I was just enjoying Mexico's intricacy and beautiful popular art. That was one of my influences. The other one was that I love movies with Tarzan. We used to go over to the forest and play Tarzan. The narration of nature has always been in my mind. I combined these two things from my childhood and the impressions I received in those marvelous places. That's more or less how I feel about my painting, and to which I have even converted all these patterns and ideas into my portraits.

Los Monos de Peru, 2020, Oil on canvas, 60” x 48”

U: How can galleries and museums be more inclusive to Latino artists, especially by putting them in permanent collections?

A: I feel that I have been able to show at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery and my work because, again, some people called me a Chicano artist. Peter Rodriguez is the founder of the Mexican Museum in San Francisco. When he gave me my first show, he asked me, "Do you want to be in the Mexican wing or the Chicano wing?" I said, "I don't know, Peter." He said, "Well, how long have you been here?" And I said, "Oh, maybe 20 years." "Then you're Chicano." It's another confusion since I love to paint how I feel at a time of things, and that's what I do, Mexican heroes and icons and people that fit in with my love for nature. Many of the difficulties people have in getting into museums are because they're too literal about bringing the culture with them. It was really exciting when recently, one of the Smithsonian pieces that returned to that has Zapata in it.

The people were surrounding my painting, and it was because of the new way I view the world. They're so used to the icons of Mexico, the Diego Rivera, and all that. This was a new way they saw that was interesting to them and how I portrayed it with my patterns. That's how I've been able to get into museums and exhibitions because I do not very literally convert the Mexican culture itself. Still, they are part of my subconscious: dreams, experiences, and my background as a Mexican.

Because I touch into many fields like Portraiture and my landscapes of jungles and scenes of ecological things, I have to say this planet is very relevant to what's happening now. Still, many people coming from Mexico are doing the same thing and have not evolved - the same symbolic things very much. I have maneuvered to express myself originally. It's a new kind of fresh art that comes to be produced by me and that museums are interested in, but the new Mexican Museum in San Francisco is going to open pretty soon, and they already have me scheduled for that. I have been donating paintings to the Mexican Museums both in Chicago and San Francisco. Of course, the Smithsonian now has three of my works in it. It's a lot of work I've done since I was a kid until now. I have evolved.

A lot of opportunities are opening up with these museums. There's going to be a Latino museum in Washington, D.C., so many people find that these new museums will be more inclusive because many of them, Mexican museums, and Latin American museums are opening. Of course, they'll pay much more attention to our work than before.

Suquamish Waters, 2018, Oil on canvas, 60” x 96”

U: What is your process like when selecting artwork for an exhibit?

A: I don't select anything because I just paint all the time. Sometimes I'm painting, and an hour later, I'm amazed at what I am painting. Then, when there is an interest, I'm going to have a big retrospective at the Museum of Northwest Art here in Washington. They have a curator that likes to choose the imagery for the shows. The idea that I have a project to do something doesn't apply to me. I just paint everyday ideas that come out and also that they come from another source. That's where artists think they're crazy because they can not explain those sources or where they come from. When the Moscone Center opened in San Francisco, they were interested in me doing a mural for them, but there was no way I could do that because I rely on that source as it comes into my hand and my brush and into the canvas. I did a collage of jungles and things like that that didn't work. I didn't get accepted. Now that I have created all these years of recognition, they don't ask me for sketches or ideas because they know they already trust that what I'm going to do will be okay.

Mandala, 1985, oil on canvas, 60" x 60"

U: What does a typical day look like? Can you describe it?

A: Well, I paint from nine o'clock in the morning till 4:00 daily. I'm so dedicated to my work that even when I go on a trip and arrive in Seattle, I immediately go to my studio because I have all these ideas in my head. My suits are full of paint because when I come from an opening or a thing, I run into the studio, and then paint gets into them because I have to develop that idea right away before it disappears. It was very therapeutic because I had an anxiety episode, and they gave me two cortisone shots for my hands. It drove me crazy for a month and a half. I couldn't even sit down, but painting was the only thing that relieved that anxiety. It's very therapeutic for me to paint because it calms me down. It's sort of a meditative feeling about it.

Totem, 1990, oil on canvas, 72" x 48"

U: If painting is life for you and what you strive to do most, what is life without painting?

A: Well, I wouldn't know because I painted most of my life, since I was 12 years old. When I travel to Spain or to shows, I am entertained by how busy I get with an exhibition. Since I'm involved with my art continuously, I don't know what it would be like without painting, but I wouldn't be very happy.

El Huipil, 2017, oil on canvas, 48”x36”

U: What literary figures have inspired your artwork and paintings the most?

A: Well, I have painted a lot of Mexican icons, but the one that I repeat constantly is Frida Kahlo. That is because she uses such wonderful Mexican attire, the decorative dresses I use as patterns. Sometimes she becomes ghostly because of the patterns blended with the forest, the jungle, the leaves, and everything else. She's an icon that reminds me of my mother because my mother was the one that told me how to do art and paint, but she said for me in Mexico, there's no chance that I will be an artist because it's so difficult to get into it, to be accepted. She's a symbol of women's suffering that they can not accomplish things because of the few opportunities offered to them.

She's also a symbol of the jungle because she's beautiful and she loves nature. She was surrounded by animals. She was interested in agriculture and the fields and the things that inspired her. She's perfect for me. I have done more paintings of Frida than anybody else.

Zapata was also interested in the land, and I have icons of Neruda because I love his descriptions of jungles and the rainforest. I have them. Lately, I have done portraits of three Justices. In the State of Washington, the Supreme Court, I became a friend of Steve Gonzalez, now the Chief Justice in the State of Washington. He came over one day and said, "I want to ask you a favor." He says, "Can you do a portrait of Justice Smith?" Because the son went with him to the Palace of Justice, where they had all these stiff portraits of all white people, and the son said, "How come there aren't any people of color here, dad?" That's why he came over to do Justice Smith because he was a mentor to many minorities, and he was black.

El Joven Zapata, 1995, oil on canvas, 28”x22”

There are a lot of new portraits being done for minorities to be inclusive. I did my first portrait. Then I did another of Mary, who is half Chinese and half Mexican. The last portrait was of Steve Gonzalez. That has revolutionized the court because now they're going to be part of the Palace of Justice. Things like that excite me because they are movements of recognition for the Latinos and Mexican people that contribute so much to this society.

U: When living in Mexico City as a teen, what vivid memories have influenced how you see the world and create your artwork?

A: I was very interested in the jungle, and I was very interested in Mexican architecture and all the Mexican culture. When I was 12 years old, my grandfather convinced the school of fine arts to accept me. After looking at what I was doing, they decided to let me in there. That's how I started being interested in expressing myself and how I feel about the culture. When my father was 90, he started becoming really interested that I was an artist because I disobeyed him. He wanted me to be an engineer or an architect. When I came to the United States, I said, well, I'm over here now. I have to decide what I want. I went to the School of Architecture at the University of Washington. Soon I decided that I wanted to really do more than that. I was envious of all these artists in the art department wearing overalls and throwing paint on the canvases. I said, boy, I can do that. That has been sort of who I am, not really what I do.

Nuestra Senora de la Selva (Our Lady of the Jungle), 1989, Oil on canvas, 72” x 48”

Painting is just something that is part of me, I carry my culture with me, but I see the world also. Not only Mexico but all the world that interests me. I was in Japan. I was influenced by Japanese art. I was in Korea, and I was in Spain. All those things go in that library of my subconscious. When I'm painting, it pours out as patterns or ideas.

Of course, being a child in Mexico has a lot to do with my work. Some people think I have essays from art historians that now want to say that I am a true Mexican painter. The United States now wants me to be an American painter. It's kind of interesting how when you get recognition, they want to own you, but before that, they don't pay any attention to you, especially in Mexico. Nobody knew about me for many years until my uncle, who was in the editorial part, suggested I should do a book and an exhibition there. More and more, I'm getting more and more recognition in Mexico, where I was with Diego Rivera and other great Mexican painters. It is wonderful that before I pass into another world or into infinity, I will leave a lot of my work, which I donate to many museums that can't afford it. I want to leave all that because a lot of people watch my work all around the world; then, it is part of opening the doors for Latinos to be represented and all these places because of the bias that, oh, we are farmers.

There is so much more than that. It's incredible the amount of Mexican talent. When I go to Mexico, I come back loaded with ideas. That's how I've been influenced by many things in many aspects of nature and the world.

Diego and Frida, 1998, oil on canvas, 60" x 42"

U: What is the essential part of the creative process for you?

A: Like Picasso said, “inspiration exists, but you hope it catches you while you're at work.” Everything influences you, like music. I have to have music to paint. I get inspired every day by walking in the woods and the parks and watching animals and birds, and things like that interest me. But like I said, it's very difficult to express all these mysterious things that make you evolve into a painter and how it starts as a canvas into which I do an abstract painting first with different colors. Afterward, that becomes the background of the painting. Then I use lines to create forms. Of course, all of these areas change according to the background color. That's all I can tell you about that

Pantano, 2013, oil on canvas, 12" x 48"

U: Your use of colors is so vivid and intense. How does that choice come about when painting, or is it just spontaneous?

A: When I was at the University of Washington getting my Master's Degree, they told me, "Your colors are too intense. Don't you realize you're in the Pacific Northwest? Here we are influenced by the orient, and you have very subtle colors, browns, grays, and everything. You are using such an intense color." I told them, "Well, that's never going to change because it is not what I think; it is how I feel.” Those colors are innate. It probably comes from growing up in Mexico and the intense colors and the beauty, including the houses and architecture. All these wonderful colors. I remember creating eggs sometime in the year where you create all these beautiful eggs with purples, greens, and yellows and fill them up with confetti, and then you go around this Plaza, this center of the city. When you see a beautiful girl, you crack an egg on their head.

You know? It is very innate in me. I don't think what color. I think that I have learned a lot about colors like yellow advances and blue recedes and aerial perspective into which the farther you go, the grayer and bluer gets. When you want something near you, reds, yellows, and things like that become very close to you. I don't think about, oh, I'm going to make a painting that is going to be blue, or I'm going to make this and that. No, I'm always mixing the paint according to how I feel, which comes out in that kind of painting. Like I told you, the underground is already painted in different colors.

Between each pattern and the other one, you create new shapes. I love that. I don't decide anything in advance. I just go to my canvas, and all of a sudden, all these things start appearing: a leaf in the forest, berries, and things like that. People say, "What kind of berries are those?" I would say, "My own. I don't know where they came from."

Xochiquetzal, 2014, oil on canvas, 26" x 22"

U: What musicians do you listen to when you paint? Or who are some of your favorites to paint to?

A: Well, I really love a lot of music. I mostly love Jazz and, Latin American music, Mexican music. According to the rhythm of the music, sometimes I follow my brush with the music. It all depends if I want some quiet background music or something real like mambos and things that make me paint real fast.

Red Pony, 2015, oil on canvas, 36" x 60"

U: Where do music and art intersect for you? Where do they find their common ground, where they're familiar, where you can paint with your emotions and express yourself creatively?

A: Well, it's another mystery, not something directly, but they have the same idea that all their arts have and to which you get illuminated by those ideas that come in the middle of the night for scientists and the music is the same thing. Composers all of a sudden hear these melodies in their head that translate into pieces of music or something. Writers - the same thing. They start writing, and all these things start coming out. With the music, ..... that's why Jazz has improvisations and things like that. They're creating sounds and compositions that are really beautiful. The music puts me in a meditative state that I love to be in because then I get that connection that artists have, to which the basketball players say you are in the zone when they're throwing balls at the basket and hitting all the time.

That's where it comes. I just put the music on and start painting that relationship with my work. That relaxes me from the monkeys in my head always thinking of negative things sometimes. I get rid of all that stuff with the music and the painting.

Mother and Son, 2009, oil on canvas, 60”x48'“

U: What does making art mean to you?

A: Survival because psychologically, I need it, and success makes you be able to buy paints and to buy brushes and canvases and feel good that you have all those things. Because when I first started as a kid, my grandfather bought me some tiny oil paints, and I would open them up to get the last piece of pigment out of them. Now I feel really wealthy to have tons of tubes of paint and brushes, and it makes me feel really good. I have a lot of commissions from people now, especially portraits, which I never considered myself a portrait painter, but it works really well when I know the person and the family because I know so much more that inspires me to paint. But usually, I don't take that many commissions of portraits, but more or less, right now, they're considering me for a large work for a children's hospital in San Antonio. They love how my paint attracts children. Children love my work, and hospitals love my work because sick people need some encouragement, and they find that in my paintings, the feeling is that the world is beautiful and that although it has a lot of dark space in it, living is worthwhile.

For more information about Alfredo, please visit his site.