A Needed Conversation with Halim Flowers

Courtesy of the artist

Halim Flowers is and visual artist, spoken word poet, author, publisher, fashion designer, and activist based in Washington, DC. In 2005, Halim started his own publishing company, “SATO Communications,” SATO being an acronym for Struggle Against The Odds. Learning entrepreneurship from selling crack cocaine in the streets at the age of 12, he transferred that ambition for self-enterprise to spread his message of love beyond the walls that sought to make he was invisible. Flowers has published eleven books covering the genres of poetry, self-help, financial literacy, and his memoir “Makings of a Menace, Contrition of a Man.” Halim’s art has been exhibited both in solo shows and group shows internationally at galleries and art spaces such as DTR Modern Gallery (Boston, New York, DC, West Palm Beach), The Bomb Factory (London, UK) - Love Is The Antibody, By The People x Monochrome Collective Art Fair: Collectors' Preview, MoMa PS1 (Queens, NY) - Marking Time: Age of Mass Incarceration, Different Trains Gallery (Atlanta, GA), Metro Pictures and he has forthcoming exhibits at The Stella Jones Gallery (New Orleans, LA), Sade (Los Angeles, CA)

In 2016, DC local legislators proposed a new bill to allow those convicted of an offense committed while they were under the age of 18 to petition the court for resentencing and release after serving 20 years imprisoned. Ironically, this bill would not apply to those that had already been convicted as juvenile lifers in the 80s and 90s before the enactment of this law. Through my contacting the Mayor and all of the DC City Council members, having someone to read my personal testimony at the public hearing for this bill, and staging a social media campaign to have DC citizens testify at the public hearing in support of making the new law retroactive, on April 4, 2017, the Incarceration Reduction Amendment Act(IRAA) was enacted into DC law to apply retroactively to any person that had been convicted of a DC offense before the age of 18.

In the year of 2018, Halim was sent back to the DC Department of Corrections from the Federal Bureau of Prisons for my resentencing process pursuant to the IRAA legislation. While at the DC DOC, Halim enrolled in the Georgetown Prison And Justice Initiative to become a credit-earning student at Georgetown University. He was able to serve as a mentor in the Young Men Emerging unit inside the DC DOC, a carceral community for young adults detained under the age of 25 modeled after the therapeutic corrections culture of other western developed nations in Europe.

On March 21, 2019, after serving 22 years and two months behind bars, he was released back into society. Since his release, he has worked with Kim Kardashian for her documentary “The Justice Project,” done a spoken word performance with Kanye West at his famous Sunday Service, received the Halcyon Arts Lab and Echoing Green fellowships, and spoken at panels at universities and conferences around the country about the impact of the arts and entrepreneurship to correct our criminal injustice system.

I had the honor and pleasure to ask Halim some questions about how poetry allows him to talk about emotions, what can be done differently about the prison and jail systems, what goals and inspirations he had for starting his own publishing company, and so much more.

UZOMAH: How much time should an emerging writer or poet set aside daily to write?

HALIM: Well, I think it's relative to the individual situation because someone like me who started writing poetry during the beginning stages of my incarceration where a lot of my time was spent in solitary confinement for 23, 24 hours a day. So I had a lot of what people would say disposable time to dedicate to my practice, where I didn't have to go to work or anything like that, go to school. Where another person's situation is out in society, they may not have as much available time as I had. So I would say that I wouldn't be rigid and set a certain numerical value. But I think the emergent or the beginning writer, or poet, should definitely dedicate enough time to where they feel an ache in their hand from either writing or typing. If not daily, every other day, at least, where you start to feel discomfort for how much work you put in on the keyboard or with a pen and pad.

U: How does poetry allow you to talk about emotions that would otherwise not be invited for discussion?

H: Well, as a socially constructed man, just my gender alone, inherent culture in our society in America, that convinces me that anything that I feel should be concealed and suppressed, and any emotional expression is made synonymous with being feminine or being like a woman. And then it's like this subtle, this latent pressure to not act like a woman or a homosexual. At least, that was my situation growing up. I think the world is a little more liberal today. So for me, with poetry and letter writing, because in prison, when I first came to prison, we didn't have access to emails or the internet or anything like that, so the bulk of our communication was handwritten letters and “collect” calls, which were expensive. So we did a lot of handwriting. So, for me, poetry became a way in which I could artistically express myself and how I felt about others and life in a way in which, as a socially constructed man, I was never encouraged to be so liberated in that way. It opened me up in so many other areas in my life. It allowed me to develop a personal [inaudible] that I have today, what people would say is transparency. People would say it would make me vulnerable because I'm so transparent, but I don't think it makes me vulnerable because I think vulnerability is a trigger word to encourage people to subtly suppress how they really feel. I just think it makes me authentic. So poetry definitely removed the manacles of this gender-based male cultural encouragement to suppress how men and I are supposed to feel and put forth this bravado, this machismo, to which I no longer ascribe. Poetry allowed me to express how I feel and not feel no sense of shame about it without trying to question my manhood, my gender, or my sexuality.

U: Do you have any forthcoming future projects or forthcoming publications?

H: What's funny is that in prison, I started my own publishing company and I published and released 11 books. And since I've been home, I transitioned into paintings and photography and documentary film and fashion, so I haven't been really moved to write like I used to anymore. Where I do have a potential project in the works with a potential deal with Simon and Schuster, where it's a book about me as a socially constructed black person in the fine arts world. So it's not in alignment with the poetic written expression or essay writing and things that still even I don't practice as much as I used to, but still are very dear to me.

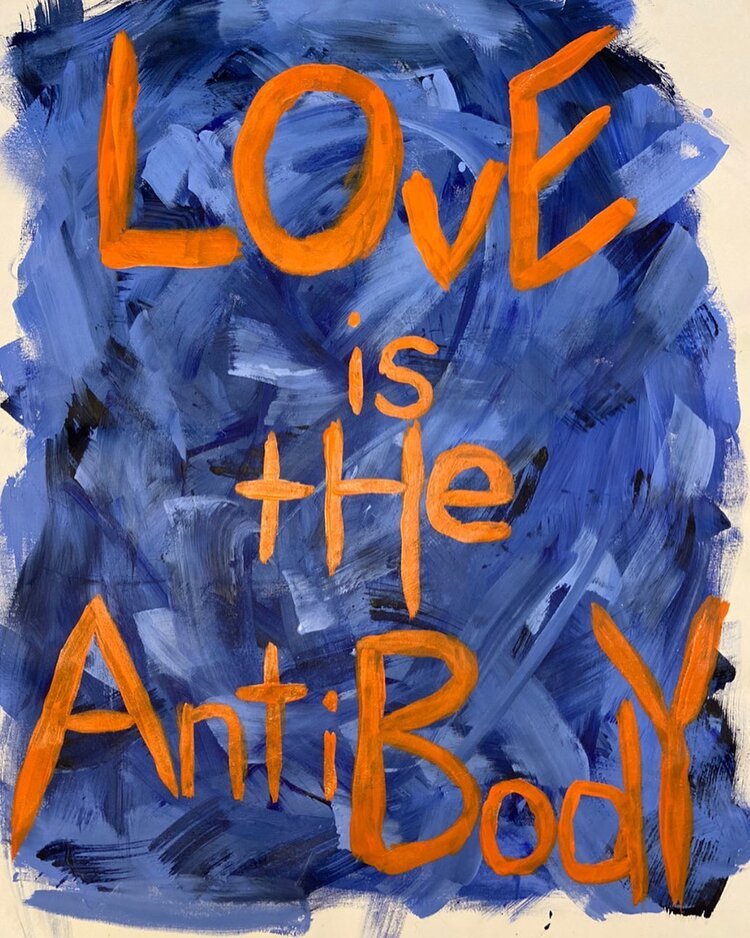

Love is the Anti-Body, Arcylic on canvas, 2020, 40x31

U: What were some of the goals and inspirations behind forming your publishing company?

H: Well, the title, the publishing company was called Struggle Against the Odds. And for me, I saw that it was millions of other similarly situated people like myself in bondage, in the penal system, and whether they were guilty or not wasn't really of a consequence to me. I started the Struggle Against the Odds Publications because I wanted to give the voice a platform to myself and others who I believe, even though they were incarcerated, their individual stories had value.

Their poetry had value. Their short stories and fiction novels had value. And just due to their nature of being incarcerated, and if you add on top of that their race and class before their incarceration, their stories and talent were being buried alive. And I knew that my seeking to tell my story and then eventually build a platform to help others to share their written talents, I knew that it would definitely be a struggle against the odds. It'd be an uphill battle, but nonetheless, it was one that I was willing to fight, even if I had to fight it going up the hill. So that was my inspiration for starting SATO, which is an acronym for Struggle Against the Odds Publications.

U: What are you currently reading?

H: I'm currently reading a book called The Power of One. It's kind of like one of my art collectors who's into the Kabbalah Jewish teachings sent that to me. And I'm reading another book called How to Love by a Vietnamese Buddhist monk named Thich Nhat Hanh. And the third book I'm reading is a book called The Kybalion. It is a very interesting book about mental transmutation and alchemy, meaning transforming base ideas and attitudes and transforming them into golden philosophies and attitudes and vibrations. It's all about the law of attraction and vibrations and synergy and polarity. And a very interesting book, but that's just three of the books. I'm reading like five different books. I just can't remember them. One of them was called The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. Something like that. I tend to read like five or six books at a time.

U: How did writing prose and poetry during your sentence help you during that period of time? How does writing still help you now?

H: Well, during that time, it gave me a ... Because in the system, you don't have physical access to your loved ones. You're denied any form of intimacy and privacy, so it kind of makes you self-centered in a way, and I didn't really know how to articulate what I was going through at that time in the way I do now. Being a child, 16, and facing the rest of my life in prison, poetry and writing gave me an avenue to express how I was feeling. And besides this raging, riding, and throwing tantrums, and how it helps me now, it drives my visual art. In my visual art, I've never been one who drew or sketched anything like that. I started painting during the pandemic, so when you look at a lot of my paintings and my fashion design, it's textually driven.

And I tell people when I do my design, my sneakers, my clothes, or my paints in my visual works, I don't begin with an image idea in mind. I begin with a philosophical concept, an intellectual ideal, and I create a sneaker or hoodie or a painting around an intellectual ideal or moral principle. And most of my work is textual. A lot of writing ... Because it took me a while. I didn't understand why they kept referring to me as a street artist in the fine art world. And I was like, "Well, I'm not a street artist. I never spray painted or anything like that." I couldn't understand it. But street artists in Western identification of visual art engage in a lot of texts visually. And that is my practice. So writing today is, a lot of times for me now, it's in my paintings.

War of the Worlds, Acrylic and oil sticks, 36x60, 2020

U: What draws you to create with the visual arts, and how does it give you another way to express yourself?

H: What drew me to the visual arts initially was seeing Basquiat's artwork; seeing Basquiat's work is definitely what... Because I mean, I heard JayZ rapping about him, and in prison, I didn't have the internet or the smartphone to see who he was or his work. So when I had the opportunity to come home, I read an article about him in the Wall Street Journal, didn't have his work, and had a picture of him. So I had an opportunity to see him. I was like, "This is who the rapper is rapping about?" I didn't know he was a black guy cause he sounded French or something. So I didn't know he was a Haitian Dominican brother. So I said, "when I go home, I want to see his work."

And I came home, had an opportunity for a year to be free before COVID, and I got the opportunity to see his work. And I really dig this work, and I watched his documentaries, and I said... I would go to the museums when I came home, the art galleries, and none of the art I saw really spoke to me. I really wasn't enjoying what I was seeing. And I was like, "there has to be some space, in the visual art world, whether it was the museums or the galleries that would appreciate the type of art that I would appreciate." And so I said, "When given the opportunity, I'm going to throw my hat in the pot and just start out, maybe just painting my poetry?" Because I don't know how to draw anything, like that profession, I do have a developed philosophy that I express poetically.

I would just put that on the canvas. I didn't even know of that Christopher Wall and Ed Ruscha, the famous textual artists. I didn't even know of them at that time. I just saw what Basquiat did, and I liked it, and I felt like I could do it in my own way. And that's what kind of gave me the impetus to want to get into the art world, just going to the museums and really seeing people who didn't look like me were just able to put banana peels... Bananas in a booth at an art [inaudible], get international attention. Or just splash paint on the canvas with no meaning and be able to receive critical praise, so I just felt like it had to be other people like me who would value work that had intellectual meaning or was even written on the canvas. And that's what gave me the impetus once the quarantine happened. It gave me a little time to be still and to start painting.

Queen Breonna, 2020, aryclic and oil sticks on canvas, 32x29

U: Where do art, poetry, and activism, intersect for you?

H: For me, I believe that product development is the greatest tool for activists. And I look at paintings; I look at sneakers, I look at luxury streetwear, I look at books, all these things are products, cultural assets. And by me really caring about love and equity and people, humanity, and having no faith in the traditional tools that we are encouraged to use, like the ballot or the bullet. And I really...

Want to help? Do my part to help humanity, to help the world. And I believe in the sneaker culture, and I believe in streetwear culture, I believe in fine art culture. I believe in documentaries, I believe in poetry, and books as useful tools and shifting people's paradigms. And these are my weapons of mass construction, that I use because I believe in them. And I don't believe in the other things that I was encouraged to use, the ballot or the bullet, so yeah.

I am free because of she, 2020, oil sticks on newspaper digital print, 20x24

U: How can more jails and prisons help prisoners find reform through education by creating programs similar to the one you were able to earn cause credit through the Georgetown Prison and Justice Initiative?

H: The first step is restoring the Pell Grant for incarcerated people. In college, education is referred to as higher learning for a reason. It raises one morally and academically to a higher standard of thinking, speaking, and living. And if a person has done a crime.

Then obviously, they have some social ill that needs addressing, and just throwing them in prison and allowing the internal conditions that they have education-wise or social-wise to perpetuate from providing them an efficient remedy. I find that to be criminal and inefficient and a betrayal to the American public because the whole point of the criminal legal system is supposedly public safety. And to say that, and then to have an individual punished for an offense that deems them as a public threat and not providing them with the resources to remove the danger from the person, it's a waste of taxpayer's money, which I pay a lot of now. And it's just a waste of, first and foremost, the human potential to be great because I can look at an individual like myself who was deemed irredeemable and a menace to society and a monster and look at all the dope stuff that I'm doing today. So, that shows that if I can do it, I'm not a Marvel comic superhero. If I can do it, other people can do even more if given access to the resources and support, so that's how I feel about that.

U: How does creating give you more reason to live and more purpose?

H: For me, that's just... I don't know. I just “don't want to do nothing else,” but... people consider it work, but it's labor, “I don't want to do nothing” but manufacture, paint and poetry, and sneakers and books. It's a real live addiction for me. So I don't know life without that purpose, because I've been doing it for... It's been such an intricate part of my life for so long that I don't know a life without it.

Still I shine, 2020, Acrylic, oil sticks on canvas, 72x72

U: What would you tell 16-year-old you today?

H: Oh, many people in life encourage you and others to value the opinions of how others feel about you, what you want to do with your life, and who you genuinely want to be. And some of the choices you make in an attempt to impress others incur severe consequences. And when you go through these consequences, 99.9% of the people you're setting out to impress will not be there for you in your time of need.

So it would be in your best interest to live your life, to feed yourself first and foremost. And when you do that, you will find freedom in life and "being" that most people will never experience in their life. And until you have that, then you really won't have anything. You live in prison, within your mind, because you don't have the liberty to be yourself. And once you give yourself the freedom to be yourself, you will be surprised at some of the amazing things you will be able to accomplish. And that's what I would tell myself. It just took some time for me to understand that.

Please visit his site for more information about Halim’s activism, writing, and art. You can find him on Tumblr, follow him on Instagram and Twitter, and watch his videos on YouTube.