A Healing Conversation with Ariella Wertheimer

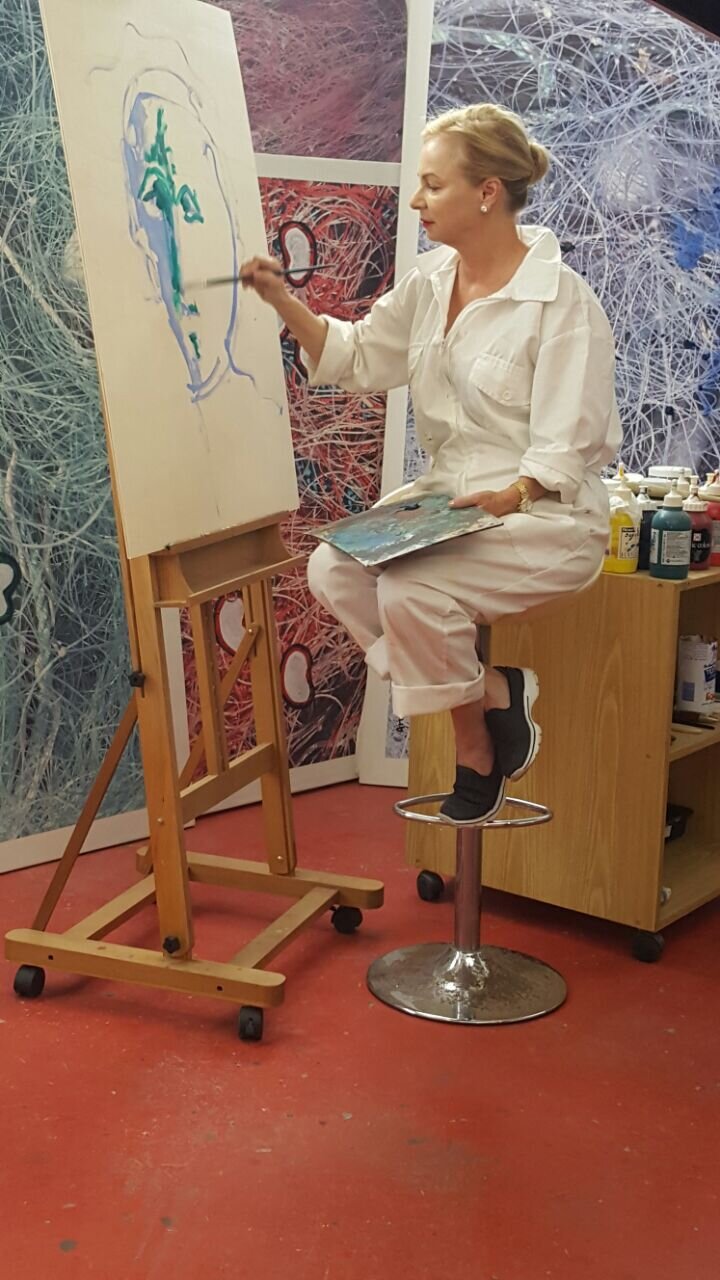

Ariella in the studio, Photo by Lena Gomon

Ariela Wertheimer is a multidisciplinary artist based in Israel. Art Realisatta is honored to have her for the first interview. When Ariela is not describing her surroundings one graceful stroke at a time, she is finding and embracing the healing aspects of art. I got to talk with her about her thoughts on women in the art industry, her artistic process, and how art has led to some major points in her life. Ariela’s art is in many private collections and has been exhibited throughout Europe including Palazzo Mora, Beit-Hagefen, and elsewhere.

Uzomah: How does the history and culture of Israel play a part in your art?

Ariella: The study of history has connected me to my roots and has given me a different perspective on life today. My work conducts a dialogue with where I live, the place’s history, and the complexity stemming from the identity and multiculturalism of the people that live here. My parents were also immigrants, and through them, I experienced difficulties in language, culture, and adjustment. In my series of light works “The Freedom to Let Go” from 2016, I discussed local history by combining the personal stories of Jaffa residents with the local landscapes. I tried to convey the feelings of the refugees and immigrants who arrived in Israel. The sense of foreignness, the new smells, the temperature, and the feeling of suffocation and confinement each of us carries inside and is shaped by our past and present experiences.

U: When addressing the many subjects you tackle through various mediums from photography to painting, how do you select a medium which is best to get the message across that you want to convey?

A: I create my artworks in layers. The aspects of time, concealment, and discovery are the essence of the work, and through them, I explore the topics of journey, time, and processes. By using multiple mediums, I am able to create layer on top of layer and tell a more complex story. For example, in my works from the series “The Freedom to Let Go,” I used photography, painting, and light. The combination created a sense of depth and continuance.

In the exhibition “Skin,” which I presented in Venice in 2019, I combined layers of photography and painting to discuss the hidden and the visible, concealment and discovery. The material Resin, which was used as a final layer in some of the artworks, created an additional barrier and sealed some of the works.

“Black Skin,” mixed media, 2019, “180cm by 220cm” Photo by Lena Gomon

U: What has been one of your favorite exhibits and why?

A: “Skin” is the exhibition I cherish the most. It emerged from my personal story that I repressed for years and has a connection to the Me Too movement. In this series of works — which includes paintings, a large-scale photo, and video art — I created a sort of analogy between my skin and photos of the exterior of “sick” boats. The boats undergo cleaning and repainting in a place called “HaMispana,” a shipyard in Jaffa, where they are turned seaworthy again. The link between two parallel stories of two different worlds has allowed me to discuss the process of injury and recovery.

U: What can art teach us about humanity? How has art answered some of your questions about humanity?

A: Today, in times of pandemic and great loneliness, people’s need for a common language, a community, and a discourse is evident. And art does that. It connects people, invokes thought by creating a discussion, and draws attention to universal messages beyond time and place — beyond the present moment. There is something comforting in the timelessness of art, the sphere in which it takes place, something reassuring: things are happening here and now, but they are also part of a greater and longer historical context. From a more practical perspective — now, as galleries and museums have been opened for virtual viewing — anyone can become familiar with the culture and language we all share.

“Kaleidoscope,” 2019, mixed media, 80cm by 100cm” Photo by Lena Gomon

U: What advice would you give to a young artist in Israel who is just starting out?

A: Excellent question. The life of an artist, not to mention a female artist, is challenging in many ways. When I was young and wanted to go to art school, my parents objected and said: “a profession like that does not pay the bills.” Later, after a military career as an IDF officer specializing in radiology (photography has always been a part of me), I fulfilled my dream and went to study art. My breakthrough was late in life, around the age of 60. So, my advice is to go with your truth, and know that it’s never too late.

U: How can women play a larger role in the art industry?

A: When I was young, to reach a senior position, I had to be several times better and more scholarly than any of the men. Now, for the most part, society has made progress in terms of gender equality. My advice — as a woman, use your skills, initiative, and systems thinking. It always helps.

In the art world, when it comes to the art market and museum collections and exhibitions, everything is still far from equal. And yet, there are more women in senior positions — in curatorship and museum management — which is already a sign of change. If these women, who are in key positions, were to make sure to advance good female artists, purchase their works to collections, and research and introduce more excellent female artists from our history, I have no doubt in my mind that change will come.

U: Who are some of your favorite artists and authors, or poets?

A: That is a question I am asked a lot. The artist I admire most is Picasso. His ability to see the human world through such a different prism, his inner ability to disassemble and reassemble, and obviously exhibit this process to the viewer in a versatile and relevant manner. My favorite poet is Wisława Szymborska. She has a direct, original, and simple style. Her poetry talks about time and history but also about people and relationships; she has the ability to capture the moment.

U: Have you faced any roadblocks as a female artist? What has been a seminal experience for you as an artist?

A: In my case, the art field had difficulty accepting me because of my status, my family, the fact that we owned a network of museums. For years it made me feel insecure about publicly exhibiting my art. In recent years, I have been coping with that insecurity and fear of exposure, as I did in the exhibition “Skin.” The fear, the decision to go with it, the dialogue with the viewers. It has been a transformative experience.

“Self-Portrait,” 2019, print on canvas, “680cm by 460cm”

U: How would you describe your artistic style from when you were starting out to where you are now?

A: I started out as a figurative painter. My first experience was with a teacher who taught me to paint portraits without looking at the page, and capture movement in seconds. Over time, I realized my language is the language of abstraction and layering. This is what guides me when I paint and also in my photography. The language of the abstract transcends imagery or depiction. It can create a sensual, emotional, and philosophical experience, and engage the viewer. It also freed me from the “rules” of what’s right and wrong in art and allowed me to constantly explore new materials and techniques.

U: How do you know when a painting or work of art is done that you are creating?

A: Most of the time, it’s just an inner feeling, but there are also mistakes, and then I go back to the work and change it. Many times, while correcting the work, I find the path of self-growth.

U: How do you feel your art contributes to society?

A: Since I love cooking, I will use a term from that world: art, in my opinion, is like spices. It gives the flavor — the substance — to our world. From a global perspective: in the biblical story, the tower of Babel fell because humans stopped speaking in a common language. Visual art, much like music, and dance, are art forms that bridge language and hold our culture together in times of crisis. And this is my job, as an artist, to be part of that.

Ariella in the studio, Photo by Lena Gomon

U: How has art and the process of making art been a therapeutic vessel for you?

A: Creation, for me, is a way to communicate non-verbal thoughts, emotions, and world views. It is also therapeutic and allows me to overcome fear and shame. Through my exhibition “Skin,” I was able to cope with the rape I endured in my youth. And in much the same way, the origin of my new series — “recovery process” — on which I am currently working, is my husband’s cancer.

U: During the Holocaust, a lot of art collections from Jewish families were seized and then sold to museums. How do you feel about the current situation and conflict facing museums and the origin of how they received artwork? As an artist how does this make you feel?

A: Since ancient times, occupiers tended to plunder art and wipe out any trace of the occupied culture. Through the destruction of the culture, they attempted to upset the very soul of the occupied people.

Although repatriation of art to the rightful owners, or their heirs, can be a painful reminder of loss, war, and pain, it is also essential for the preservation of a culture and its origins. It is the national museums and the state’s responsibility to keep investigating and restoring the plundered art to us, as our cultural heritage.

For more information and updates on Areila’s work please visit here.