Calder : Un effet du japonais

Cover of Calder: Un effet du japonais, 2024 © Pace Gallery

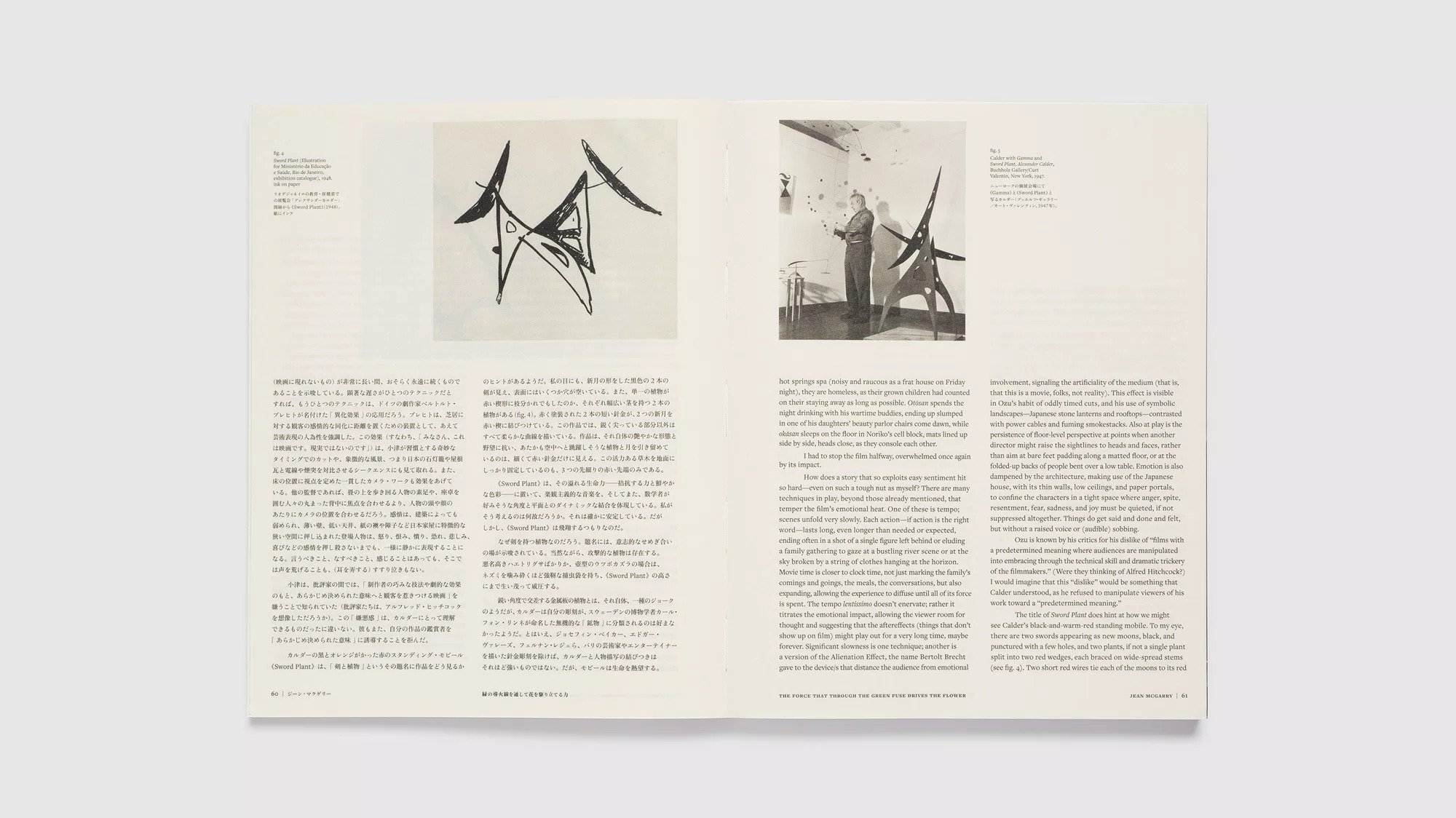

This new catalogue from Pace Publishing—available in English and Japanese—accompanies Calder: Un effet du japonais, a landmark exhibition of Alexander Calder’s work co-presented by Pace and Azabudai Hills Gallery in Tokyo.

Courtesy of © Pace Gallery

Exploring the enduring resonance of the American modernist’s art with Japanese traditions and aesthetics, Calder: Un effet du japonais marks the first exhibition dedicated to Calder’s work to be mounted in Tokyo in nearly 35 years. Our publication features writings by Calder Foundation President Alexander S. C. Rower, who curated the exhibition in Tokyo; architect Stephanie Goto, a longtime Calder Foundation collaborator who has created a bespoke design for the show featuring elegant and modern references to Japanese architecture and materials.; Pace CEO Marc Glimcher; Susan Braeuer Dam, Director of Research and Publications at the Calder Foundation; poet and essayist Jane Hirshfield; author Jean McGarry; and Akira Tatehata, a distinguished poet and critic and the Director of the Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, in Japan.

Courtesy of © Pace Gallery

“To understand Calder’s art we must approach [it] in a spirit of meditative introspection. There’s a subtle harmony in our experience of his work that has echoes and parallels—a gracious relationship—with centuries of Japanese expression.”

Courtesy of © Pace Gallery

“If poetry is what happens when subjective expression is abandoned, then a mobile that surrenders to the wind— a mobile that’s abandoned to the wild—is a poem.”

Courtesy of © Pace Gallery

Publication Details

Text by Alexander S. C. Rower,

Susan Braeuer Dam, Marc Glimcher,

Jane Hirshfield, Jean McGarry,

Stephanie Goto, Akira Tatehata

Design by Tomo Makiura with

Mine Suda Takamizawa and Alexis Liebes

2024

Softcover

184 pages

8.5 x 10.75 in.

About Artist

Best known for his creation of the mobile, Alexander Calder is one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century. Calder was born in 1898, the second child of artist parents—his father was a sculptor and his mother a painter. In his mid-twenties, he moved to New York City, where he studied at the Art Students League and worked at the National Police Gazette, illustrating sporting events and the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Shortly after his move to Paris in 1926, Calder created his Cirque Calder (1926–31), a complex and unique body of art. It wasn’t long before his performances of the Cirque captured the attention of the Parisian avant-garde.

In 1931, a significant turning point in Calder’s artistic career occurred when he created his first kinetic nonobjective sculpture and gave form to an entirely new type of art. Some of the earliest of these objects moved by motors and were dubbed “mobiles” by Marcel Duchamp—in French, mobile refers to both “motion” and “motive.” Calder soon abandoned the mechanical aspects of these works and developed suspended mobiles that would undulate on their own with the air's currents. In response to Duchamp, Jean Arp named Calder's stationary objects “stabiles” as a means of differentiating them.

Calder returned to live in the United States with his wife, Louisa, in 1933, purchasing a dilapidated farmhouse in the rural town of Roxbury, Connecticut. It was there that he made his first sculptures for the outdoors, installing large-scale standing mobiles among the rolling hills of his property. In 1943, James Johnson Sweeney and Duchamp organized a major retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which catapulted Calder to the forefront of the New York art world and cemented his status as one of the premier American contemporary artists.

In 1953, Calder and Louisa moved back to France, ultimately settling in the small town of Saché in the Indre-et-Loire. Calder shifted his focus to large-scale commissioned works, which would dominate his practice in the last decades of his life. These included such works as Spirale (1958) for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris and Flamingo (1973) for Chicago’s Federal Center Plaza. Calder died at the age of seventy-eight in 1976, a few weeks after his major retrospective, Calder’s Universe, opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Cover of Calder: Un effet du japonais, 2024 © Pace Gallery